In the history of beekeeping the name Anton Janša (or Janscha, born 20 May 1734 in Bresnica; died 13 September 1773 in Vienna) is writ large. Janscha rates an early mention here as he represents everything that is good about beekeeping - innovation, creativity, applied arts and the effortless marriage of scientific methods and folk traditions (even though, today, we may not associate all of these terms with mainstream beekeeping).

Janscha was a painter, a keeper of folk lore, a renowned apiarist and a designer - he designed hives as well as the houses to keep them in.

He was, in short, a guru.

Janscha was born in present day Slovenia and trained as a painter. He came from a long line of beekeepers and, unsurprisingly perhaps, became a distinguished beekeeper himself. He published two very significant works in German: one on beekeeping in general and one on swarming. He had the distinction of being appointed the world's first full-time, beekeeping lecturer by the Empress Maria Theresa. In 1770 he was promoted to the position of Imperial and Royal Beekeeper and kept hives in the royal gardens.

In the lands we now know as Austria, Anton Janscha was to beekeeping and honey production what his contemporary, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was to classical music.

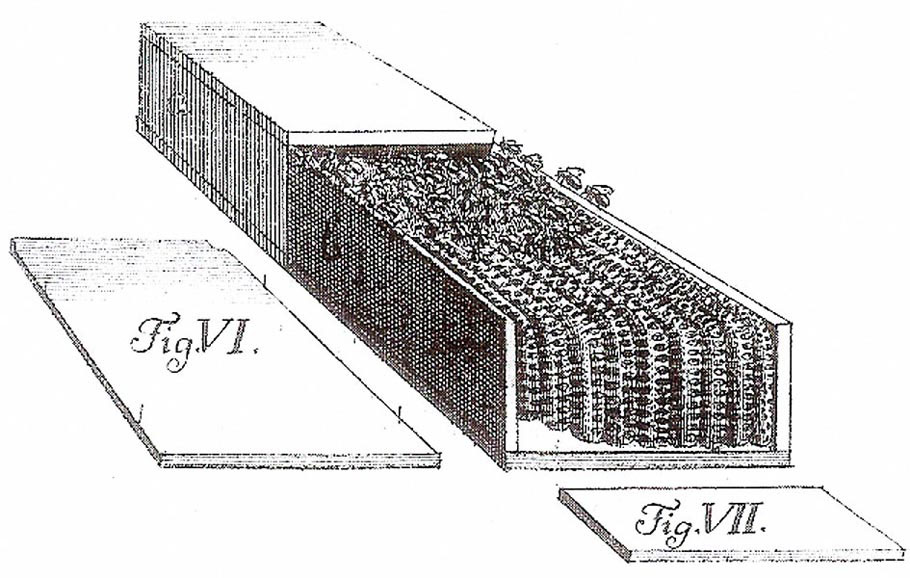

Janscha's hive designs were horizontal and a precursor to top-bar hive design. They were 79cm long, 32cm or 37cm wide and 16cm high. These hives could be inserted into a small bee house (shown above), or a horse drawn wagon; like drawers into a chest. He taught the significance of moving hives to suitable pasture, to chase what we now call the honey flow. Like modern/Langstroth hives seen today, Janscha's hives were stackable. They also featured holes on the top and bottom of the boxes, that could be opened and closed, to allow movement between the two. This allowed colonies to grow in Spring and Summer, much like adding supers achieves today. He also split large colonies by separating the two boxes, and referred to this as artificial swarming.

A board, inside the hives, could be slid backwards and forwards to reduce the volume for small swarms (today we would use the compact nuc hive to achieve this).

Janscha was extremely innovative and the preeminent beekeeper of his day. But he was also an artist and man of good humour. As a painter he could decorate his own hives, as was the fashion at the time. These paintings were rendered on the front panel of the hives (see Fig. VII above) and often depicted secular or religious motifs. But my favourites, pictured here, are the satirical and folky types that depict animals in human roles or refer to folk stories - like the hunter's funeral with the procession lead by the forest animals.

They were installed in a grid formation (as pictured above), with sixty or so miniature, often humourous or deeply spiritual painted scenes welcoming and entertaining beekeepers and onlookers alike. No doubt his precious Carniolan honey bees (Apis mellifera carnica Pollman) also used the variation in the fascia boards to assist in finding their hive among the many.

Science and applied arts. Design innovation and the vernacular.

Like I said: the man was a guru.

References:

Dr Eva Crane's 'The World History of Beekeeping and Honey Hunting', Routledge, 1999.

Prof Gene Kritsky's 'The Quest for the Perfect Hive', Oxford, 2010